The war in Ukraine is leading to a fundamental reshaping of the defence industry in Europe, given the scale of drone use and widespread loss of tanks and other armoured fighting vehicles.

The number of armoured fighting vehicles lost by both Russia and Ukraine since the conflict started two years ago “is basically the equivalent of all of Europe’s armoured fighting vehicle production”, said Phillips O’Brien, professor of strategic studies at the University of St Andrews.

Speaking in a webinar organised by HanETF, O’Brien said there had been at least 3,000 “visually confirmed” losses of main battle tanks by Russia and 827 by Ukraine, although actual losses are likely to be much higher. “We’re looking at 4,000 main battle tanks lost on both sides, which is a number that would dwarf European defence capacity to replace.”

The UK, France and Germany currently only operate around 700 main battle tanks between them, he added.

If losses of armoured personnel carriers and other fighting vehicles are added in, the number tops around 10,000. This begs the question as to whether a new kind of war has emerged “where we don’t need to build or invest a huge amount" in heavily armoured vehicles, O’Brien said.

Increased drone use is the reason for such heavy losses. Although drones have been used in wars before, the scale of their deployment, production and destruction is unprecedented. Tens of thousands of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are being lost each month and Ukraine has set an optimistic target of building a million this year.

“Even if they get anywhere close to that figure, that would make UAVs one of the largest built components of modern war.”

Meeting pledges

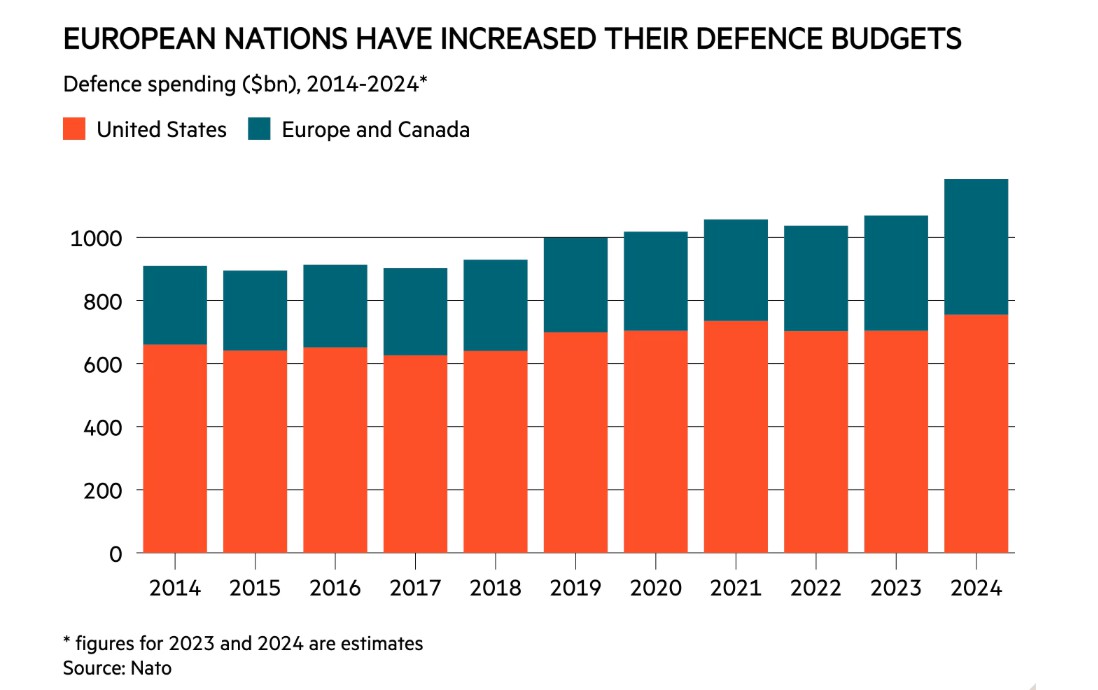

Defence spending is ramping up across Europe. The number of countries expected to meet their commitment to Nato to spend at least 2 per cent of gross domestic product on defence will more than double this year, the organisation said.

Some 23 out of 32 members of the pact will meet the goal this year, an increase from just 10 last year. Nato has forecast an 18 per cent increase in spending this year, up from 9 per cent last year.

The UK’s three main political parties have all committed to increasing defence spending to 2.5 per cent of GDP, although the Conservatives are the only party to set a timeline to achieve this. Its manifesto not only pledged to hit 2.5 per cent by 2030 but to lobby for all other Nato members to do the same.

The UK has historically been one of the countries that has met the target, and currently spends around 2.3 per cent of GDP on defence. Other major member nations are falling well short – Italy is expected to spend less than 1.5 per cent of GDP this year, Canada less than 1.4 per cent and Spain less than 1.3 per cent, Nato’s figures show.

Labour’s manifesto acknowledged the changing nature of war, including the greater use of hybrid warfare, and pledged to conduct a strategic defence review within its first 12 months. The Liberal Democrats pledged to “tackle longstanding problems in defence procurement”.

Europe’s defence companies have re-rated since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Shares in Germany’s Rheinmetall (DE:RHM) have increased fivefold, while those in Italy’s Leonardo (IT:LDO) have doubled.

In the UK, BAE Systems (BA.) shares are up 128 per cent, Babcock International’s (BAB) have gained 75 per cent and Qinetiq’s (QQ.) 45 per cent.

The strong tailwind that increased spending will provide “is now largely priced in for most UK defence companies, as shown by increased valuation multiples”, said Jamie Murray, an equity analyst at Shore Capital.

For example, shares in BAE Systems traded at 13 times earnings as the war broke out, a discount to US peers such as Northrop Grumman (US:NOC) and Lockheed Martin (US:LMT). They now trade at a premium, at 19 times earnings, and Murray said that, given the company’s sheer size, it is unlikely to grow at a rate that would outpace the wider market. But he still expects the sector as a whole to outperform the market over the medium term.

Many companies face a few years of increased capex to meet additional demand. Once complete, the investment will underpin their long-term potential, he said, citing Hampshire-based Chemring (CHG) as an example.

Chemring is currently spending £200mn to ramp up the production of energetics used in artillery shells, whose stocks have been severely depleted. This will add £100mn to its top line and £30mn to its operating profit once work completes in 2028.

Although Chemring's valuation multiples might appear elevated in the short term, “if you look further out towards 2028, it is clear the current valuation is very appealing”, Murray said.