Alexander Markus, leader of the 105-member association, said that he sees similarities between today’s Ukraine and Poland as it was in 2001 — three years before Ukraine’s smaller but richer western neighbor joined the European Union and NATO.

Germany didn’t take the competitive threat of Poland seriously back then, but has since learned that Polish business “is very competitive, especially in the food processing area,” Markus said, and that Poland is also ahead of Germany in some ways.

“Germans only noticed the Polish boom afterwards,” he said. “Ukraine is undergoing a situation like Poland did 15–20 years ago. It’s very much the same today. Poland is actually a manufacturing platform for the European Union … Ukraine will go the same way in the future.”

In a Sept. 27 interview with the Kyiv Post, Markus described a largely silent investment boom under way in parts of Ukraine, led by German and other investors, and not completely reflected in official statistics.

Top German sector

“Our estimate is that we have 30,000 workplaces in central and western Ukraine just in the German automotive component industry,” Markus said.

“Nobody knows about this. We have a huge problem that Ukraine doesn’t tell enough about itself in Western Europe.”

And, in some cases, German companies like to stay silent about their successes in Ukraine to keep away competitors. “If you found the golden spot, would you go home and tell about this?” Markus asked. “You aren’t crazy, are you?”

He said some German companies have hired scouts to explore the regions of Ukraine, looking for promising new places to open factories or plants because of a developing shortage of qualified labor in western Ukraine. He expects that, as Ukraine’s roads and other infrastructure improve, companies will migrate from western to central Ukraine.

Decentralization a plus

He said that decentralization of government is a big plus for economic development because it forces regional governments to compete with each other for private investment.

“Decentralization is the best thing that can happen in Ukraine,” Markus said. “Let’s say I’m building a new plant in the region. I get all my permits on the spot. The head of the (local government) administration understands that I will pay taxes, everything ‘white.’ I pay everything officially. He is struggling to support me because he understands that if he can’t convince me this is the right spot, I’m moving to the neighboring region. Decentralization is a good mechanism, and it works.”

Biggest investors

Possibly the biggest German employer in Ukraine, with 8,000 people in two plants, is Kromberg & Schubert, which makes complex wire cable networks for Germany’s vaunted car manufacturing industry. Kromberg & Schubert have plants in Lutsk and Zhytomyr.

But close behind is LEONI, another Germany automotive components manufacturer, which will open its second Ukrainian plant, in Kolomyia, adding to a workforce that includes 7,000 employees in its plant in Stryi, a Lviv Oblast city of 61,000 people near the western border.

Two other giants among German businesses in Ukraine are: Metro Cash & Carry, the Dusseldorf-based food and retail giant, which has invested an estimated $500 million; and Knauf, the Iphofen-based manufacturer of drywall and other building construction materials, which has invested an estimated $350 million.

A strong component of German investment in Ukraine is at the smaller end. Estimates of the number of German businesses in Ukraine range from 1,200, according to the Germany Embassy, to at least 2,000 active companies, by Markus’ estimate.

Of the German-Ukrainian Chamber of Industry & Commerce’s 105 members, Markus classifies 2/3 as middle-to-large companies and 1/3 in the small business category. The organization gets 40 percent of its funding from the German Ministry of Economy and Energy and the rest from membership dues and service fees.

Any business operating in Ukraine is eligible for membership. Currently, 70 percent are German companies, 20 percent are Ukrainian, and 10 percent are from other European countries.

Studied Russian

Markus first arrived in Ukraine in 2006, working in private business development for the European Commission, and stayed for 18 months. “I liked it quite a lot,” he said.

He became deputy head of the German-Russian Chamber of Industry and Commerce in Moscow, where he worked for nearly four years before returning to Kyiv in 2011. From the Lower-Saxony region of northern Germany, Markus has a degree in business administration and also studied the Russian language.

Improve image, brand

Ukraine needs to change its image — and, in part, its reality — of a corrupt country with big security risks.

“Ukraine is not telling the Ukrainian story in Germany, or not enough,” Markus said. “You hear much more about the Ukrainian story from other countries telling the Ukrainian story in Germany,” including Russia.

And it’s hurting business. Markus recalled one German automotive component producer telling President Petro Poroshenko that he could build an additional three or four plants in Ukraine, but automobile manufacturing customers in Germany “do not allow having more projects in Ukraine because of the image of Ukraine, and because the security evaluation is too bad,” even though western Ukraine is 1,000 kilometers from the Russian war front.

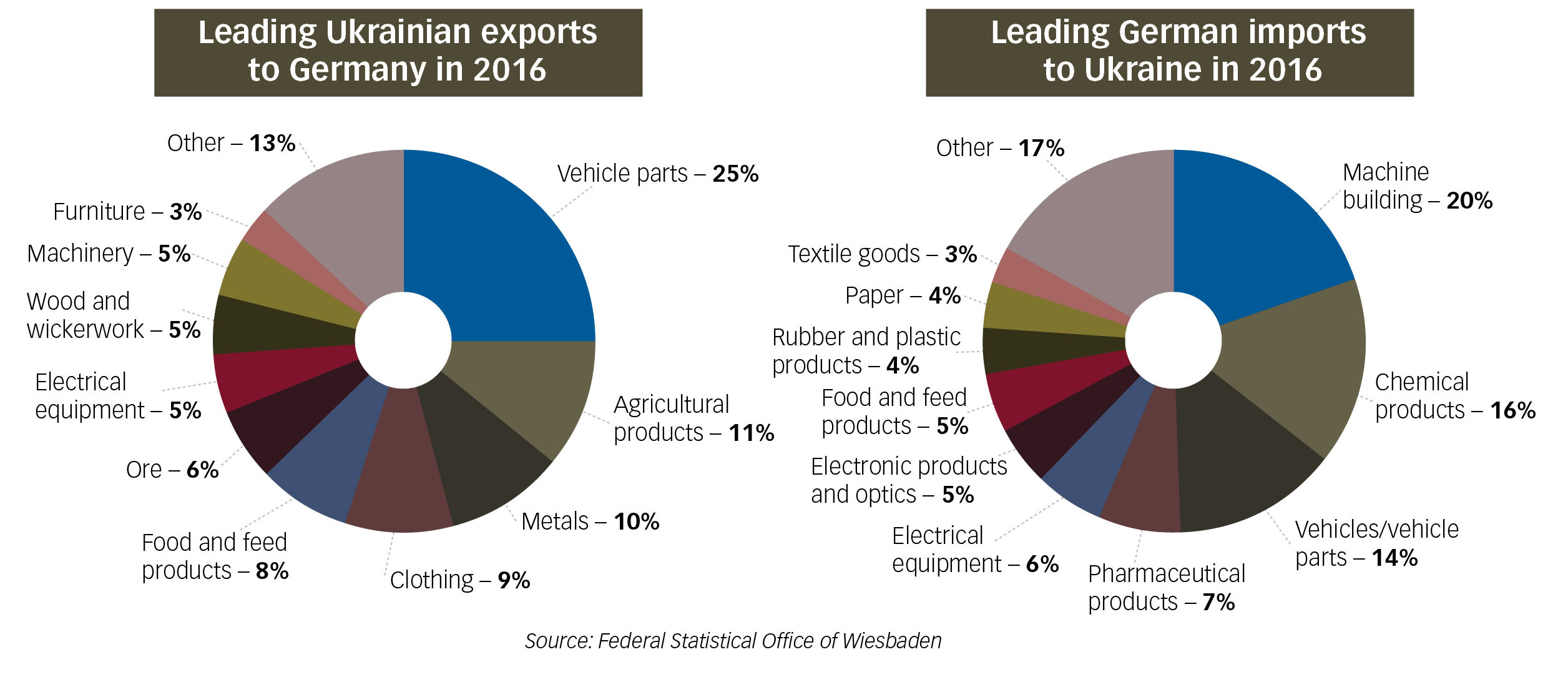

Ukraine’s trade with Germany is picking up in both directions – hitting an estimated $6.3 billion in bilateral turnover in 2016, with German exports to Ukraine still dominating the trade at $4.2 billion and only $2.1 billion in Ukrainian exports to Germany. However, in contrast to recent years in which Ukraine’s exports were dominated by steel and metals, automotive components are now Ukraine’s top export. On the German side, advanced machine-building equipment takes the top category.

Markus said that Ukraine needs to be much more active in other areas, including product branding and promoting its strengths abroad. He is a strong proponent of Ukrainian-German cooperation at the regional, rather than capital, levels. He also said that private business, not government, should drive the development agenda.

The next step for private companies is to organize at the regional level and develop cluster initiatives to share experience.

“That’s how we’re doing industrial development in western Germany,” Markus said. “It’s not for state to decide what is to be developed. The state is not expert enough in this area.”

Moreover, he said, the Ukrainian government simply doesn’t have the money to fund an export promotion program “with billions of hryvnia in the nearest future.”

Ukraine also needs to develop stronger brands for finished food products, where higher profit margins are made, rather than simply relying on exporting less profitable raw commodities.

InVenture Investment Group has a success experience in supporting German investors in agriculture sector in Ukraine.

If you need support in entering Ukrainian market please contact us: [email protected]

Early opportunities

Many German companies came to Ukraine more than a decade ago, long before Ukraine’s free trade agreement with the EU, which only went into effect this year, and they stayed. They saw the opportunities early: low production costs, an EU border and wage levels “even more than 10 times cheaper” in some areas than in the EU.

Holding back new German investors is “a very difficult security situation and political situation,” Markus said. “In German business, long-term planning is very important. If they are not sure they can plan for 15–20 years, they might not come in.”

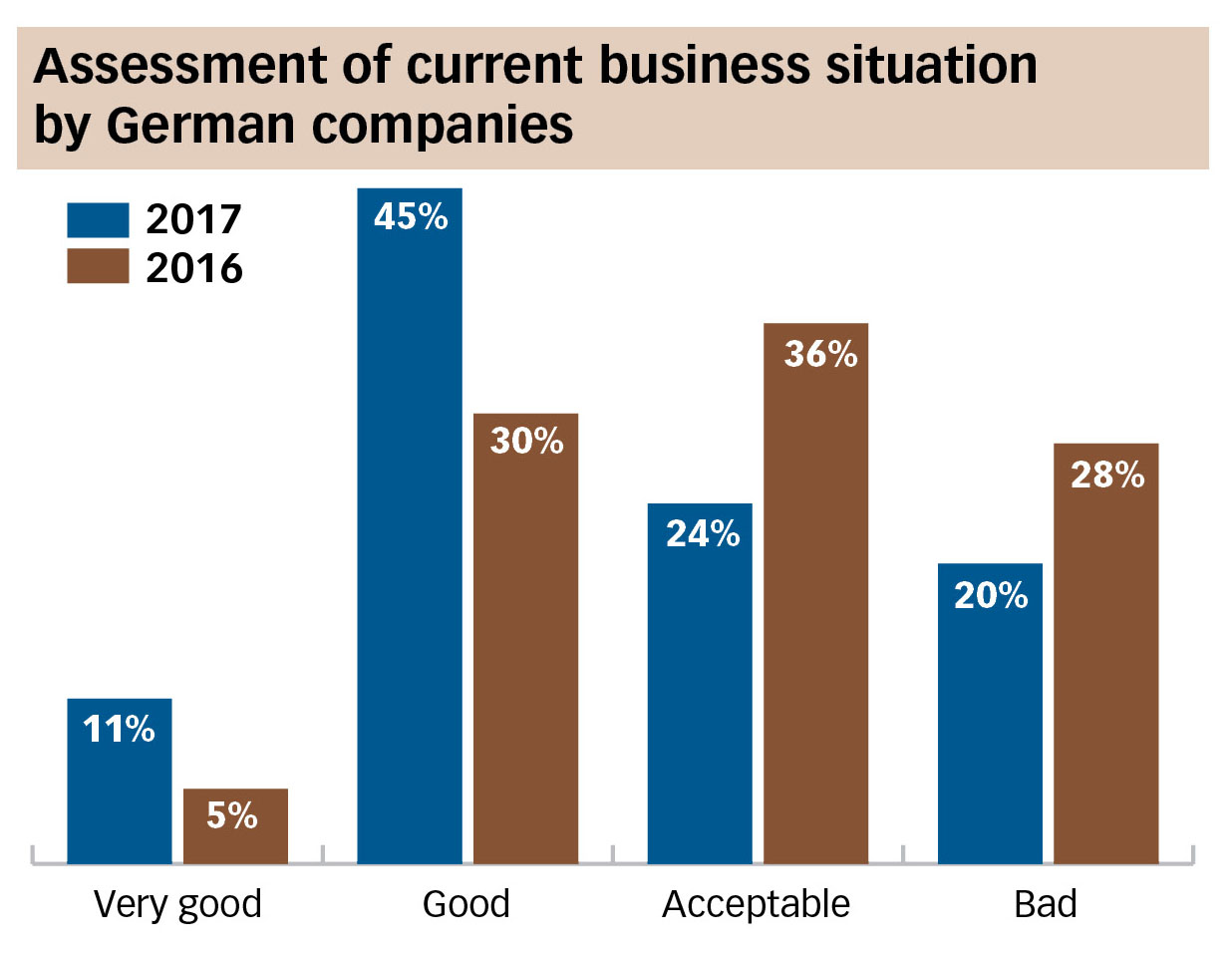

But those who dared to come to Ukraine are feeling good.

“What we see today is that the existing German investors are expanding and building new plants,” he said. “The mood is absolutely optimistic,” he said, fueled by a 25 percent increase in German exports to Ukraine in the last year.

The character of Ukraine-German trade is also encouraging. While Russia mainly exports oil and gas to Germany, Ukraine’s exports are more diversified — led by auto components, agricultural commodities, foodstuffs and so on.

And German investment in Ukraine and Russia is also different.

German companies surveyed by the German-Ukrainian Chamber of Industry and Commerce say business has improved in the last year.

German businesses are investing in Russia just to sell inside the country while, in Ukraine, “companies that are investing here are investing to export — to get the higher value added in the EU.”

Consequently, manufacturing from Ukraine aimed at the EU market “has to be much higher quality” to meet standards. German automakers, for instance, allow “no more than five parts per million in damaged products” in components. “It is one of the highest quality standards worldwide, and this is made in Ukraine.”

German exports to Ukraine are led by advanced engineering, which is an encouraging sign about Ukraine.

“This shows that Ukrainian industry is modernizing and buying high-end German engineering products,” he said.

Challenges ahead

In food, for instance, Germans are “importing more at a cheaper price. That is something Ukraine has to work on. A major task for Ukraine should be not only to deliver half-ready goods that will be processed or packaged in plants in Germany, but to develop their own brands,” Markus said. “The (highest profit) margin is in the last meters.”

While low production costs and borders with the EU are advantages, Markus said that Ukraine must do more to implement the free trade agreement to realize its advantages.

For instance, he said, “there is no single accredited food laboratory in Ukraine. Every food certificate to import to EU standard has to be done by a laboratory in the European Union. It’s ridiculous.”

In another example, he said that Cologne, Germany, each year holds one of the largest international exhibitions on food products and only last year, for the first time, did a Ukrainian representative attend.

Ukraine should make regular appearances, he said, in Germany’s regions.

“It is not enough to go to Berlin,” he said. “Real business in Germany is not in the capital.”

German approach

German businesses, he said, have mostly succeeded in avoiding Ukraine’s powerful billionaire oligarchs because the capitalists from his homeland are investing directly, rather than becoming financial investors or buying shares and forming joint-stock companies.

“They have a business idea and have a business model,” Markus said. “They are investing 100 percent on their own.” To do so, they need a land plot, legal framework, source materials, infrastructure, good workforce and markets. They are not working in areas where the oligarchs are so interested.”

Estimates of Germany’s foreign direct investment vary significantly, from $1.7 billion to $3.8 billion.

One reason is that some of the investment isn’t being counted by Ukraine, Markus said.

He knows companies that supply additives to make food tastier and other products. Some of those companies reported 30 percent growth last year in the food processing industry.

The numbers don’t show up in official statistics often because “the middle Ukrainian entrepreneur doesn’t report the real figures,” Markus said. “The major strategy is duck and cover. ‘I will not be seen because somebody might knock on the door.’ That’s why we may not see the boom.”

Source: Kyivpost