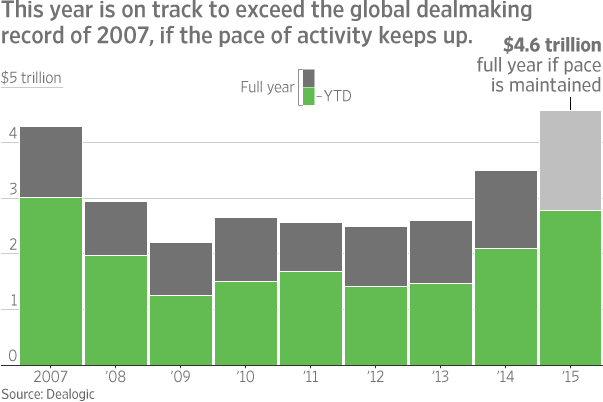

Takeover-deal announcements would reach $4.58 trillion this year if the current pace of activity continues, according to data provider Dealogic. That tally would comfortably exceed the $4.29 trillion notched in 2007, a record year for deal making.

There is no assurance the intensity will continue. Deals tend to beget deals, and much depends on executives’ mind-set and their stomach for risk, both of which can quickly turn. Lately, chief executives have shown a swagger when it comes to deals. But that attitude could revert to what deal makers call a “pencils down” mind-set as a result of, say, a sharp increase in interest rates, an economic downdraft or geopolitical instability.

Around this time eight years ago, deal activity was way ahead of where it is on the year now, surpassing $3 trillion compared with the $2.78 trillion of announced deals and offers so far this year. Yet volumes tapered off when the easy credit that fueled the deal market began to dry up in the summer of 2007 as the housing market cracked. The financial crisis followed.

For now, though, deal makers are in heady times. The tie-ups come as companies, after years of cost-cutting during the recession, search for ways to boost growth and find further cost savings in an overall sluggish economic environment.

Berkshire Hathaway Inc.’s $32 billion deal to buy industrial company Precision Castparts Corp., announced Monday, was the latest example of pursuit of growth through megadeal making. The takeover is the largest in Berkshire’s 50-year history and comes as Berkshire leader Warren Buffett has focused on big deals to help move the needle on growth at the $354 billion conglomerate.

Several trends are creating ripe deal-making conditions, bankers, analysts and investors say. The slowing pace of profit and revenue growth is one.

Corporate bottom lines have been squeezed this year by the soaring dollar—which makes it harder for companies to compete overseas—as well as the uneven economy and falling commodity prices.

Profit growth among companies in the S&P 500 is on track to fall 1% in the second quarter, after rising 0.9% in the first quarter, according to FactSet. Sales growth has been down in the first two quarters.

The trends mark a sharp slowdown from the years following the financial crisis, when profit and sales growth picked up speed. For all of 2014, S&P 500 company profit grew at a more brisk 5.5%, according to FactSet.

The shift is leaving investors starved for companies that can show growth. Deal making, investors say, is one way to deliver it.

“You’ve got very, very limited [revenue] growth for a lot of companies out there,” saidMichael Scanlon, portfolio manager at John Hancock Asset Management, which oversees $302 billion. “The fact that they can take this cash that’s earning nothing and go out and buy something—it does help to show growth.”

Merger activity, he said, has become a popular topic in meetings with management. “Nobody wants to be that company that’s being left out.”

At the same time, the economy isn’t in free fall, which gives chief executives confidence to move ahead with acquisitions with a bit less nervousness over whether they are taking on more than they can handle. Deals can be risky, both completing them amid potential shareholder or regulatory resistance, and making them pay off.

“A low-growth macroeconomic environment, coupled with opportunities to grow by adding new business lines and customers, is driving M&A,” said Greg Weinberger, co-head of global M&A at Credit Suisse Group AG. “We are on track to match or beat the 2007 high.”

Shareholders have also been rewarding some, though not all, acquirers, a phenomenon that doesn’t go unnoticed among chief executives. Relatively cheap debt, high stock prices and hefty coffers of cash on company balance sheets have provided the tools for takeovers.

Also, some say, a potential rise in interest rates has executives eager to pounce if there is a target they have been eyeing.

Borrowing costs are widely expected to creep higher in the months and years ahead as the Federal Reserve raises short-term rates as anticipated. After years of near-zero interest rates, investors widely expect the central bank to raise rates as soon as September or December. This year, the yield on the 10-year Treasury, a widely cited benchmark for borrowing costs, has risen 0.065 point to 2.238%.

“Often the economics are quite attractive because you’re either using cash that’s earning nothing, or debt that” isn’t expensive, said Brian Angerame, a portfolio manager at ClearBridge Investments, which has $117 billion in assets under management. “You also feel this creeping sense of urgency in the back of your mind because you fear that you might not be able to get interest rates this low for some period of time.”

Mr. Angerame’s funds have benefited from deal making. One stock in his portfolio is Humana Inc., which has agreed to be acquired by Aetna Inc. for $34.1 billion in cash and stock. Humana shares have risen 30% this year.

In 2007, takeover activity slowed when credit markets seized up thanks to mortgage-related woes. The turmoil led to a slowdown in leveraged buyouts, takeovers done by financiers with a heavy dollop of borrowed money, which represented a big chunk of deals in the last boom. Deal activity for years remained suppressed as companies shied away from spending and focused on hoarding cash.