Private equity buyers are missing out on the global M&A boom as they face a raft of challenges, from soaring valuations, lower returns, tougher competition and tighter rules on leverage, writes David Rothnie.

Overall global financial sponsor-related activity rose to US$273bn from US$219bn during the first quarter of 2015 compared with the prior year, but that disguises the true picture. Buyout activity was skewed heavily towards companies selling assets in their portfolios, with global asset disposals by private equity firms rising nearly 40%, the best start to the year since the buyout boom of 2007.

Private equity firms selling assets are benefiting from nearperfect conditions. Leon Black, chief executive of Apollo Global Management told a conference in April that over the last two years, his firm had sold about four times as much as it had bought and cautioned that “markets across the board are priced to perfection”. But these same conditions are proving a nightmare for private equity buyers looking to deploy a record amount of firepower.

“For financial sponsors, it is a tough time to buy assets – there are relatively few new primary LBOs coming from corporate; valuations are high and competition for assets from new types of buyers is intense,” said Alasdair Warren, global co-head of financial sponsors at Goldman Sachs.

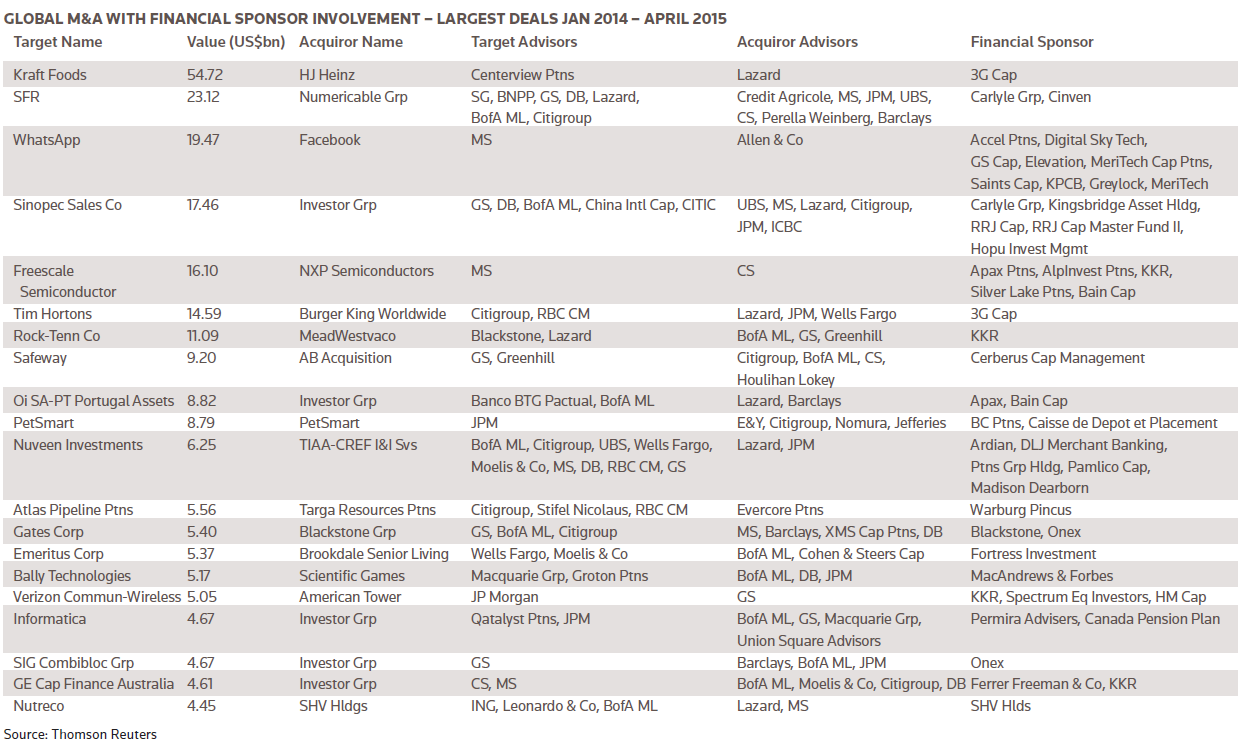

Europe is the region struggling the most. Buyside financial sponsor-M&A almost halved to US$27bn in the first quarter while in the US, where the M&A recovery is more broad-based across all industry sectors, LBOs were up 30% with US$113bn of deals announced. However, that entire rise was accounted for by a single jumbo transaction – the US$46bn buyout of Kraft Foods by Warren Buffet and 3G Capital. Asia showed the fastest growth, with buyside deal volumes rising 45%, to US$20bn, but it lags both Europe and US in terms of volumes.

Bankers are puzzled that the lack of primary acquisition opportunities comes despite a booming M&A market dominated by a rise in large deals, which usually creates a virtuous cycle for the private equity industry. That’s because big deals usually bring anti-trust issues that must be resolved, which results in disposals of prime assets. That’s not happening for a number of reasons.

Firstly, the current M&A boom has been driven by big deals in healthcare and telecoms, sectors that haven’t been traditionally attractive for private equity. Secondly, even when primary assets become available, private equity firms are being outgunned by aggressive corporate buyers awash with cash. In January, Irish building group CRH beat a private equity consortium led by KKR to the punch with a US$7.3bn acquisition of assets from Holcim, the Swiss building materials firm that disposed of the assets to meet the competition requirements of its US$40bn merger with French rival Lafarge.

Bankers expect a rise in primary deals when M&A rebounds across consumer and industrial sectors, which are more suited to financial sponsors. But a scarcity of primary assets is not the only problem.

It’s not just corporate buyers that are getting in on the action, particularly in Europe. Last year, Chinese private equity firm Hony Capital bought UK restaurant chain Pizza Express, and observers expect more Asian buyers of European assets, especially those with Asian growth angles. Sovereign wealth funds and pension funds are also becoming more active, with an increasing number of these funds now making direct asset investments rather than only investing as limited partners in private equity funds. “There are a lot more sources of capital competing for assets,” said Warren. “We used to refer to these as leftfield bidders, but they have now become main-field.”

Even more challenging is that pension funds, which favour long-dated assets such as infrastructure, operate business models that can thrive on returns that are far lower than private equity funds are accustomed to. The environment is equally challenging for secondary deals – where bidders are looking to buy assets already owned by private equity firms.

By definition, it’s often harder to generate returns on these assets, but this is compounded by the difficulty potential buyers have in competing with surging IPO markets, currently the favoured exit route for many portfolio companies “The IPO bid in Europe is being supported by very strong fund flows, particularly from the large US-based global funds” Warren said.

With such a fierce competitive arena, buyout firms are trying to shun asset auctions and are seeking out exclusive opportunities, even if it means paying a premium as they face pressure to deploy record amounts of firepower. The ability to deploy capital successfully at a reasonable pace is the life-blood of private equity, because a firm’s investment track record is one of the factors that will allow them to raise fresh funds.

“So the onus falls on origination – sponsors typically want to avoid auction processes and, in a tough investing environment with many new buyers, some are willing to pay more if they can avoid a multi-handed auction” said Warren.

Although there is an abundance of capital, banks are being forced to reign in lending. Tough guidelines from the OCC and the Federal Reserve prevent US banks, and foreign banks with operations in the US, from participating in the most leveraged deals – US leveraged lending has slumped 70% over the last 12 months.

As private equity firms scour the globe for acquisitions, they are coming to accept that in a low-growth economic environment, they will have to lower their returns if the model is to survive. In a worst-case scenario, some buyout firms could disappear altogether. “There is a bifurcation in the industry between strong firms with differentiated origination that are able to make attractive investments even in today’s tougher market and those that struggle. I think firms that can invest capital quickly and realise these investments successfully will be those that are best able to raise new funds in the long-run,” Warren said.