If you look at what’s happened in big cities around the U.S. in recent years, it’s easy to think we’re living in Startup Nation. Thanks to the plummeting cost and increased availability of digital tools, as well as greater access to early-stage funding, we’ve seen what the Economist has called a “Cambrian moment,” with digital startups “bubbling up in an astonishing variety of services and products.” The number of companies in Silicon Valley that got seed funding from investors, for instance, more than doubled between 2007 and 2012. Venture capital funding in the U.S. over the last five years has totaled a remarkable $238 billion, and 200 companies today are so-called unicorns, privately valued at more than a billion dollars each.

Meanwhile, though, a host of economic researchers have been telling a much bleaker story: American entrepreneurship is actually on the decline, and has been for decades. As the economists Ian Hathaway and Robert Litan documented in a 2014 Brookings Institution paper, the percentage of U.S. firms that were less than a year old fell by almost half between 1978 and 2011, declining precipitously during the recession of 2007-’09 with only a slow recovery after. According to the Commerce Department, the number of new businesses started by Americans has fallen sharply since 2000, and so too has the percentage of American workers working for companies that are less than a year old. Indeed, in 2013 Americans started fewer businesses than they did in 1980, when the country’s population was much smaller. This decline isn’t just due to the aging of the U.S. population—Americans of all ages just seem less likely to open new businesses than they once were. And, as Hathaway and Litan put it, the decline “has been documented across a broad range of sectors in the U.S. economy, even in high-tech.”

So has America lost its appetite for risk? Not really. It is true that the number of new businesses has fallen, but much of that decline has been concentrated in what economists call “subsistence” businesses. These are businesses whose founders have no interest in creating a big company. Their ambition is to do something they enjoy, gain some measure of financial independence, avoid having to deal with a boss, and so on. And the data is clear that in recent years, fewer people with goals of that kind have been starting businesses of their own.

A small percentage of new businesses, though, are different: from the start, their ambition is to become big. These businesses are run by “transformational” entrepreneurs—would-be Jeff Bezoses and Elon Musks—and they’re what we usually mean when we use the term “startups.” These companies represent a small fraction of all new businesses in the U.S. But historically, they’ve made what the economist John Haltiwanger and other researchers have shown are “disproportionately large contributions” to net job creation. In fact, what Haltiwanger and colleagues call “high-growth” firms (companies that are adding jobs at a rate of more than 25 percent a year) make up just 15 percent of all companies, but they account for roughly 50 percent of total jobs created. These young firms also invest more, proportionately, in R&D than older ones.

These high-growth firms, then, are the kinds of companies that matter most if we’re trying to understand the impact that startups are having on the economy and on innovation. And according to a May report from the Kauffman Foundation, such startups are being launched at a brisker rate than in recent years. Even more telling, new work by the MIT economists Scott Stern and Jorge Guzman shows that in 15 U.S. states between 1988 and 2014 there was no long-term decline in the formation of what they call “high-quality” startups. Stern and Guzman have figured out the characteristics of startups that are trying to become high-growth firms, which include being chartered in Delaware, registering for patents, and not being named after the company’s founder. What they find is that the rate at which these kinds of startups are being formed has not dropped—in fact, 2014 saw the “second-highest level of entrepreneurial growth potential” ever. In places like the San Francisco Bay Area, unsurprisingly, the rate of high-quality startup creation is at an all-time high.

But there is a catch. While Stern and Guzman show that high-growth firms are being formed as actively as ever, they also find that these companies are not succeeding as often as such companies once did. As the researchers put it, “Even as the number of new ideas and potential for innovation is increasing, there seems to be a reduction in the ability of companies to scale in a meaningful and systematic way.” As many seeds as ever are being planted. But fewer trees are growing to the sky.

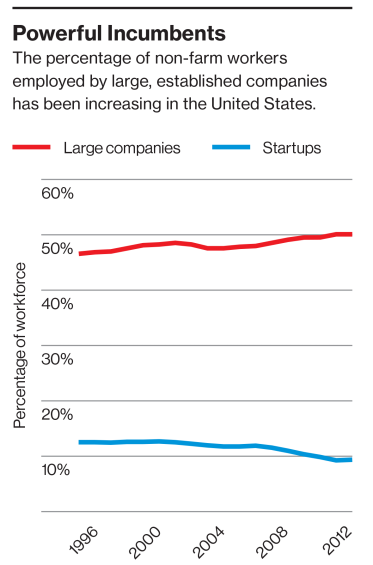

Stern and Guzman are agnostic about why this is happening. But one obvious answer suggests itself: the increased power of established incumbents. We may think that we have been living in a business world in which incumbents are always on the verge of being toppled and competitive advantage is more fragile than ever. And clearly there are industries in which that has been the case—think of how Amazon transformed book retailing, or how digital downloads and streaming disrupted the music business. But as Hathaway and Litan document, American industry has grown more concentrated over the last 30 years, and incumbents have become more powerful in almost every business sector. As they put it, “it has become increasingly advantageous to be an incumbent, and less advantageous to be a new entrant.” Even in tech, the contrast is striking between the ferment of the late 1990s, when many sectors had myriad players struggling for share, and the seeming stability of today’s Google/Amazon/Facebook-dominated world.

In the short run, this may not seem like that big a deal. After all, Google, Amazon, and Facebook are all investing heavily in R&D, and they seem as interested in pursuing moon shots as incremental innovations. These companies are also continuing to hire at a fast pace. In the long run, though, the U.S. economy needs more startups that make the leap to high-growth success, both because of the key role they play in creating new jobs and because of the way they help propel technological innovation. A 2010 study, for instance, found that incumbents tended to invest in R&D that exploited existing technologies and in incremental innovations, while startups focused more on new technologies and radical innovation. Similarly, an earlier Kauffman Foundation report noted that new companies were “more likely to enter the market with cutting-edge innovations.”

That means we don’t want the future of technology to depend on the investing decisions of a handful of giant companies. We want it to emerge out of a robust ecosystem of incumbents and startups. The story of the U.S. economy over the past century has been one of technological dynamism. Figuring out ways to foster competition and create opportunities for transformational entrepreneurs is the best way to ensure that the story of the next century isn’t one of stagnation.